This fall I had a fun literary triptych focused on our society’s consumption habits and our relationship with our possessions. I wanted to challenge myself to think expansively about why we buy things and how we decide to keep them around or not.

I started with The Minimalist Home by Joshua Becker. I have long thought of myself as having minimalist tendencies that (I tell myself) are generally thwarted by my family’s need for stuff. On the surface, this book felt aligned with my general craving for tidy desks and bare countertops.

Never in history have human beings had so much stuff inside their houses. One estimate puts the number of items inside the average American home at three hundred thousand.”

― Joshua Becker, The Minimalist Home: A Room-by-Room Guide to a Decluttered, Refocused Life

But in following it up with All Things are Too Small: Essays in Praise of Excess by Becca Rothfeld I questioned what I’m giving up by, at least theoretically, striving for sparseness. She gives multiple perspectives that by focusing on minimalism in all aspects of life: stuff, art, literature, spirituality, we are impoverishing our lives and focusing on, in the end, becoming nothing. I felt the emotional pull toward fullness and beauty for its own sake.

We are inundated with exhortations to smallness: short sentences stitched into short books, professional declutterers who tell us to trash our possessions, meditation “practices” that promise to clear the mind of thought and other detritus, and nostalgic campaigns for sexual restraint. These adventures in parsimony each make their own particular mistakes, but they also share a central failing. There is nothing admirable in laboring to love a world as unlike heaven as possible. All things are too small, but some things are less small than others. Even if paucity is inevitable, we can still fight emptiness with fullness. -Becca Rothfeld, All Things are Too Small

Lastly, Status Anxiety by Alain de Botton dives into the role that status plays in driving human decision-making and that right now, our economic position, display of possessions and leisure signaling is the primary way we now define status. He covers the speed of product cycles and the viewpoints on wealth and societal roles over time that have led us to where we are now.

Rather than a tale of greed, the history of luxury could more accurately be read as a record of emotional trauma. It is the legacy of those who have felt pressured by the disdain of others to add an extraordinary amount to their bare selves in order to signal that they may claim to love. -Status Anxiety, Alain de Botton

This last one hit home. Halloween was last week, and I disappointed myself by buying my 80s themed costume via Amazon Prime with expedited shipping. I’m telling myself I can wear the costume again in the future and that it isn’t so wasteful, but I keep thinking about the greenhouse gas emissions and the workforce implications of such a purchase.

What led me there? My desire to belong.

I have a fairly new job and there was an office Halloween costume party, and I wanted to fit in. To be seen as part of the team. But I didn’t leave time to plan for a thoughtful costume. So, I scrambled. I made a purchase out of sync with my values for the purpose of boosting my status.

The Possession Spectrum

In recent years, the discussion on consumption and how we manage our stuff has been about defining a personal philosophy for the relationship we have with our possessions.

We are a nation that tends towards extremes, and our attitudes about consumption are no exception, but wherever you are on the spectrum, you are likely doing your thing with increasing speed. Declutterers are trashing items as soon as they procure them and those who aren’t declutterers are upsizing homes and storage units to accommodate their levels of quick consumption.

I want to create space and time to align what I invite into my life with what matters

Continuums of Stuff

My reading rabbit hole has me wondering if we need more dynamic thinking on consumption than whether one is a minimalist or not. This duality leaves out the external forces and drivers that strongly influence our purchasing decisions.

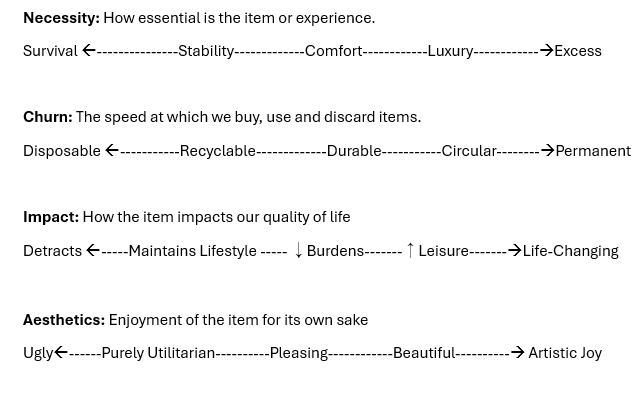

I suggest there are at least four additional continuums of consumption to consider that influence us. They are perhaps more important than how we identify on the minimalist/maximalist spectrum.

Critically considering these aspects when we are weighing a purchase would force a slower pace. Beyond just deciding if one is a minimalist or a clutter bug, it leaves room for usefulness, art and beauty, sustainability.

To train my non-reptilian brain to do this I sketched out this decision flow based on those “Continuums of Stuff” to play around with how to rationally make these decisions while under intense marketing and status pressures. I intentionally left room for interpretation because I think what is largely missing in our society is a foundation of thoughtfulness.

Stay Tuned

Netflix’s new Documentary Buy Now will begin streaming November 20th. Based on the trailer, I think it might be well worth a watch. Buy Now! The Shopping Conspiracy | Official Trailer | Netflix

Thank you for this thoughtful framework! And while the 80s costume may have been a high churn item, perhaps “are you a working super mom” should be a 5th continuum for consideration :)